Introduction to Odu Obara

The name "Obara" itself evokes images of strength, determination, and righteous force—the energy that moves mountains when necessary, that stands unmoved against injustice, and that protects the vulnerable from harm. In Yoruba cosmology, Obara is intimately connected with concepts of moral courage and righteous action—not mindless aggression or violence for its own sake, but purposeful strength applied in service of truth and justice. Just as the warrior protects their community, just as the guardian defends sacred boundaries, Obara energy enables humans to act courageously when action is required and to stand firm when firmness serves the greater good.

In the Ifa tradition, Obara is understood as the divine principle governing all forms of righteous strength and moral courage—from the personal bravery required to speak uncomfortable truths to the collective courage needed to confront systemic injustice, from the strength to maintain boundaries in relationships to the fortitude to defend principles despite social pressure, from the warrior's protective instinct to the leader's willingness to take responsibility. This Odu reveals that strength is not simply physical capacity but moral quality, that courage is not absence of fear but action despite fear, and that true power lies not in domination but in service to what is right.

When Obara appears in divination, it often signals times requiring courage and decisive action, situations where boundaries must be established or defended, moments demanding you stand firm for what you believe, periods requiring you to confront rather than avoid challenges, or circumstances where strength and fortitude are essential. Obara asks critical questions: Where in your life do you need to act more courageously? What boundaries require defending? What truth needs speaking despite your fear? Where are you avoiding necessary confrontation? How might your strength serve purposes larger than yourself?

The Obara corpus comprises 16 major divinations, beginning with Obara Meji (the double manifestation of Obara) and continuing through Obara's combinations with each of the other 15 principal Odu. Each of these divinations addresses different aspects of strength and courage—from righteous confrontation to protective boundaries, from moral integrity to warrior wisdom, from personal fortitude to collective defense. Together, they form a comprehensive system of warrior wisdom applicable to every dimension of human experience where courage, strength, and righteous action are required.

The Spiritual Essence of Obara

The Principle of Righteous Strength

At the heart of Obara lies the principle of righteous strength—the understanding that true power is not simply capacity to dominate or control, but the moral quality of knowing when and how to apply force, the wisdom to distinguish between necessary action and unnecessary aggression, and the integrity to use strength in service of justice rather than ego. This principle operates at multiple levels simultaneously. Physically, Obara governs the body's capacity for action, the muscular power to move and act, and the vitality that enables engagement with physical reality. Psychologically, it governs willpower, determination, assertiveness, and the capacity to stand firm under pressure. Spiritually, it governs moral courage, the strength to live according to truth, and the fortitude to defend principles despite consequences.

Obara teaches that strength without wisdom is dangerous. Raw power unleashed without moral guidance becomes violence. Force applied without understanding causes harm. Capacity divorced from purpose serves no good end. History is filled with examples of strength misused—powerful people who dominated rather than served, strong nations that conquered rather than protected, capable individuals who bullied rather than defended. Obara reveals that this misuse of strength betrays the warrior's true purpose and ultimately diminishes rather than increases genuine power.

True Obara strength integrates power with purpose, capacity with conscience, and force with wisdom. The genuine warrior asks not "Can I win this fight?" but "Should this fight be fought? What principle does it serve? Who benefits from this action? What are the consequences of both acting and refraining?" These questions distinguish righteous strength from mere aggression, purposeful force from reactive violence, and moral courage from ego-driven dominance. Obara teaches that the warrior who cannot ask these questions is not yet truly strong, regardless of their physical prowess or tactical skill.

The principle of righteous strength also reveals that real power often involves restraint. The warrior who must constantly prove their strength is actually revealing insecurity. The person who cannot control their aggressive impulses demonstrates lack of strength, not abundance of it. The individual who dominates every situation shows fear of equality, not confidence in capability. Obara teaches that the highest form of strength is knowing you could act forcefully but choosing not to when force isn't necessary, being capable of aggression but defaulting to peace, and having power but wielding it sparingly and purposefully. This paradox—that restraint demonstrates strength rather than weakness—is central to Obara's wisdom.

Moral Courage and Speaking Truth

One of Obara's most essential teachings concerns moral courage—particularly the courage to speak truth when doing so carries personal cost, to stand for principles when standing alone, and to confront injustice when confrontation invites retaliation. In many ways, moral courage requires more strength than physical bravery. Physical courage involves facing tangible dangers in defined moments—a battle, an emergency, a specific threat. Moral courage involves facing ongoing consequences—social rejection, career damage, relationship loss, community condemnation—for the sake of principles that others may not value or understand.

Consider the various situations requiring moral courage: Speaking truth to authority when that authority controls your livelihood or safety. Confronting friends or family about harmful behaviors when confrontation risks relationships you value. Standing against group consensus when the group provides belonging and support. Defending someone being mistreated when doing so makes you a target. Admitting mistakes when admission damages your reputation. Living according to values that society or your community rejects. Each of these situations requires choosing between comfort and integrity, between acceptance and authenticity, between ease and truth.

Obara teaches that avoiding these difficult choices has costs that accumulate over time. The truth not spoken becomes a weight you carry. The injustice not confronted becomes complicity you share. The principle abandoned for convenience becomes character eroded. The self betrayed for acceptance becomes authenticity lost. These costs are often invisible initially—internal rather than external, spiritual rather than material—but eventually they manifest as depression, anxiety, emptiness, or the deep dissatisfaction that comes from living at odds with your deepest values.

Speaking truth requires specific forms of courage. First, there's the courage to perceive truth clearly rather than seeing only what's comfortable or safe. Many people practice willful blindness—unconsciously refusing to see injustice they'd be obligated to confront if they saw it clearly. Second, there's courage to name truth explicitly rather than hinting vaguely or speaking in code. Indirect communication sometimes has its place, but real change often requires direct naming of problems. Third, there's courage to speak truth despite predictable negative consequences—knowing you'll be criticized, rejected, or punished but speaking anyway because silence would be worse betrayal.

Fourth, there's courage to maintain truth-telling over time rather than speaking once and retreating. Many situations require sustained voice, repeated advocacy, and ongoing willingness to be uncomfortable rather than single courageous moment. Fifth, there's courage to speak truth with skill rather than simply blurting accusations or dumping frustration. Obara teaches that how you speak matters as much as what you speak—that truth delivered without wisdom may do more harm than good, that confrontation without compassion often fails, and that moral courage includes taking responsibility for the impact of your words even when the words themselves are necessary.

The Warrior's Protective Instinct

Obara carries profound teaching about the warrior's protective instinct—the understanding that true strength's highest purpose is protecting life, defending the vulnerable, and standing between harm and those who cannot defend themselves. This teaching addresses common distortions about warrior energy that equate it with aggression, domination, or conquest. Obara reveals these as corruptions of warrior spirit rather than its authentic expression. The genuine warrior is fundamentally a protector whose strength serves others' safety and wellbeing.

The protective instinct operates at multiple levels. Most obviously, there's physical protection—defending against physical harm, ensuring bodily safety, and standing as barrier between threat and threatened. But protection extends beyond physical realm. There's emotional protection—creating safe space where vulnerability is honored rather than exploited, where people can express authentic feelings without fear of ridicule or manipulation. There's social protection—defending people's dignity, standing against discrimination or marginalization, and ensuring everyone has voice and representation.

There's intellectual protection—defending truth against propaganda, protecting knowledge against censorship, and ensuring ideas can be explored without persecution. There's spiritual protection—safeguarding people's right to their own spiritual path, defending sacred space against violation, and protecting communities' spiritual practices and traditions. In each domain, the warrior's protective instinct manifests as willingness to stand between harm and vulnerable, to use strength not for self-aggrandizement but for others' welfare, and to accept personal risk for communal benefit.

Importantly, Obara teaches that protection sometimes requires fierceness. Not all threats respond to gentle words or diplomatic negotiation. Some harm-doers respect only strength, some dangers require forceful intervention, and some situations improve only through decisive confrontational action. The parent who gently asks the predator to leave their child alone will fail; protection in that moment requires fierce, immediate, forceful intervention. The community that politely requests oppressors to stop oppressing will be ignored; liberation sometimes requires confrontation, resistance, and struggle.

However, Obara also teaches that fierceness must be proportionate, purposeful, and restrained. The protector who uses excessive force becomes perpetrator. The defender who doesn't discriminate between actual threats and perceived slights becomes paranoid aggressor. The guardian who cannot modulate their protective instinct becomes controlling rather than caring. This balance—fierce enough to be effective yet controlled enough to be appropriate—is the warrior's art and requires continuous refinement throughout life.

Boundaries as Sacred Territory

One of Obara's most practical yet profound teachings concerns boundaries—those invisible but essential lines that define where one person ends and another begins, what you will accept and what you won't, what you're responsible for and what belongs to others. Many spiritual teachings emphasize compassion, connection, and unity—all important qualities. Obara balances these with equally important teaching: healthy boundaries are not barriers to connection but foundations for authentic relationship, clear limits are not selfishness but necessary self-respect, and the capacity to say "no" is as spiritually important as the generosity that says "yes."

Boundaries operate in every dimension of life. Physical boundaries govern who can touch your body, enter your space, or access your possessions. Emotional boundaries determine what feelings you're willing to take responsibility for (your own) versus what belongs to others (theirs). Mental boundaries protect your right to your own thoughts, beliefs, and opinions rather than accepting others' views uncritically. Time and energy boundaries determine what you commit to versus what you decline, recognizing that every "yes" to one thing is implicit "no" to something else.

Spiritual boundaries protect your right to your own spiritual path, practices, and experiences rather than accepting others' spiritual authority over you. Financial boundaries govern lending, spending, and financial entanglement with others. Social boundaries determine what relationships you maintain, what gatherings you attend, and what communities you belong to. In each area, boundaries function as protective structures that enable authentic engagement rather than barriers preventing connection.

Many people struggle with boundaries for understandable reasons. Some were raised in families where boundaries were violated routinely, teaching them that boundaries are impossible or wrong to maintain. Some belong to cultures or communities that treat boundary-setting as selfishness, disloyalty, or pride rather than necessary self-care. Some fear that maintaining boundaries will result in rejection, abandonment, or conflict—fears often rooted in real past experiences where boundary-setting led to relationship loss.

Obara teaches that boundaries, though sometimes uncomfortable to establish and maintain, are essential for health at every level. Without boundaries, you become exhausted trying to meet everyone's needs and expectations. Without boundaries, people who don't respect you are given same access as people who do. Without boundaries, you carry responsibility for things you can't actually control. Without boundaries, resentment builds as you give beyond your genuine capacity. Without boundaries, authentic relationships become impossible because others relate to false self you present rather than real self you hide.

Establishing boundaries requires specific skills and practices. First, clarity about your own limits, needs, and values—you can't establish boundaries if you don't know what you're protecting. Second, ability to communicate boundaries clearly, directly, and without excessive explanation or justification. "I'm not available for that" is complete sentence that doesn't require lengthy defense. Third, willingness to maintain boundaries despite pressure, guilt-tripping, or emotional manipulation from others who benefit from your lack of boundaries.

Fourth, capacity to tolerate discomfort and conflict that sometimes arise when you establish boundaries with people accustomed to unlimited access. Fifth, self-compassion when you notice boundaries you should have maintained but didn't, or times you compromised limits you intended to hold. Boundary-setting is skill that improves with practice rather than capacity you either have or don't. Sixth, regular review and adjustment of boundaries as circumstances, relationships, and your own needs change over time.

The Teaching of Measured Response

Obara carries sophisticated teaching about measured response—the warrior's wisdom of matching action to situation rather than applying maximum force to every challenge, distinguishing between situations requiring fierce confrontation versus gentle approach, and developing capacity to modulate strength appropriately. This teaching addresses tendency toward either excess or insufficiency in responses to difficulty: some people default to overwhelming force for minor problems while others fail to apply necessary strength even when seriously threatened.

Measured response begins with accurate assessment. What is actually happening? How serious is this situation? What are the real stakes? What are likely consequences of various responses? Many conflicts escalate because people respond to imagined threats, perceived slights, or projected fears rather than actual circumstances. Someone cuts you off in traffic and your rage response treats it like life-threatening attack rather than momentary inconvenience. Friend cancels plans and you interpret it as fundamental betrayal rather than simple schedule conflict. Measured response requires seeing clearly before acting rather than reacting from triggered emotional state.

Second element involves understanding gradations of response. Between passivity and all-out confrontation exist many intermediate options: verbal boundary-setting, removal from situation, requesting third-party mediation, tactical retreat followed by strategic planning, warning before consequence, limited engagement rather than full involvement, and many others. The warrior who knows only all-or-nothing response—either complete submission or total war—lacks crucial skill development. Obara teaches that most situations call for responses in middle range rather than extremes.

Third element concerns timing. Sometimes immediate forceful response is crucial—delays allow harm to occur that quick action would prevent. Other times, immediate response would escalate unnecessarily while delayed response allows cooling of emotions and emergence of better solutions. Sometimes problem requires sustained campaign rather than single action. Sometimes issue resolves itself if given time and space. The wisdom of timing—knowing when to act immediately, when to wait, and when to engage in ongoing way—is essential warrior skill.

Fourth element involves aftermath consciousness. What happens after you respond? Every action creates consequences that ripple forward. The person who wins every battle through overwhelming force may find they've lost the war by creating enemies, burning relationships, or establishing reputation that prevents future cooperation. The person who always responds gently may be taken advantage of or fail to prevent harms that firmness would stop. Measured response considers not just immediate situation but longer-term patterns and relationships.

Developing capacity for measured response requires several practices. Regular self-observation about your typical response patterns—do you tend toward excess or insufficiency? Practice with low-stakes situations to develop skill before high-stakes moments require it. Study of how others handle various challenges, noting what works well and what doesn't. Consultation with wise advisors who can reflect perspectives you might miss in heat of moment. And cultivation of what might be called "emotional sobriety"—the capacity to feel strong emotions without being controlled by them, to acknowledge anger or fear while choosing responses based on wisdom rather than reactivity.

Leadership and Taking Responsibility

Obara carries important teaching about leadership and responsibility—the understanding that true leadership involves taking responsibility not just for your own actions but for outcomes affecting those under your care, that authority and accountability are inseparable, and that the leader's role is fundamentally about service rather than status. This teaching addresses common distortions where people seek leadership positions for prestige, power, or privilege while avoiding the responsibilities that authentic leadership entails.

Leadership in Obara's understanding is not primarily about position or title but about function and impact. The parent leads their children, responsible for choices affecting young lives. The teacher leads students, accountable for learning facilitated or hindered. The community member who speaks up leads others toward truth. The person who acts courageously leads by example even without formal authority. The friend who intervenes in harmful patterns leads toward health. Leadership emerges wherever someone takes responsibility for outcomes beyond their own immediate personal benefit.

Taking responsibility is perhaps leadership's most defining characteristic. It means acknowledging when your decisions or actions contributed to problems rather than deflecting blame. It means accepting consequences rather than evading them. It means prioritizing others' welfare over your own comfort when you've accepted leadership role. It means admitting mistakes openly rather than covering them defensively. It means staying present through difficulty rather than abandoning ship when situations become challenging. Leaders who avoid responsibility betray the trust placed in them and cause harm beyond what any single mistake would create.

Obara also teaches about responsibility's limits. You're responsible for your own choices, words, actions, and their reasonably foreseeable consequences. You're not responsible for others' choices, feelings, or reactions beyond what your actions directly caused. You're responsible for creating conditions where people can thrive but not for whether they choose to do so. You're responsible for giving your best effort but not for outcomes you cannot control. Learning to distinguish what you're genuinely responsible for versus what belongs to others or to circumstances beyond anyone's control is crucial for sustainable leadership.

The teaching also addresses leadership's relational dimension. Authentic leadership creates more leaders rather than maintaining dependent followers. It develops others' capacity rather than keeping them subordinate. It shares power rather than hoarding it. It serves the led rather than expecting the led to serve leader's ego. The leader guided by Obara wisdom measures success not by personal achievement but by flourishing of those they serve, not by control maintained but by autonomy enabled, not by status achieved but by positive impact created.

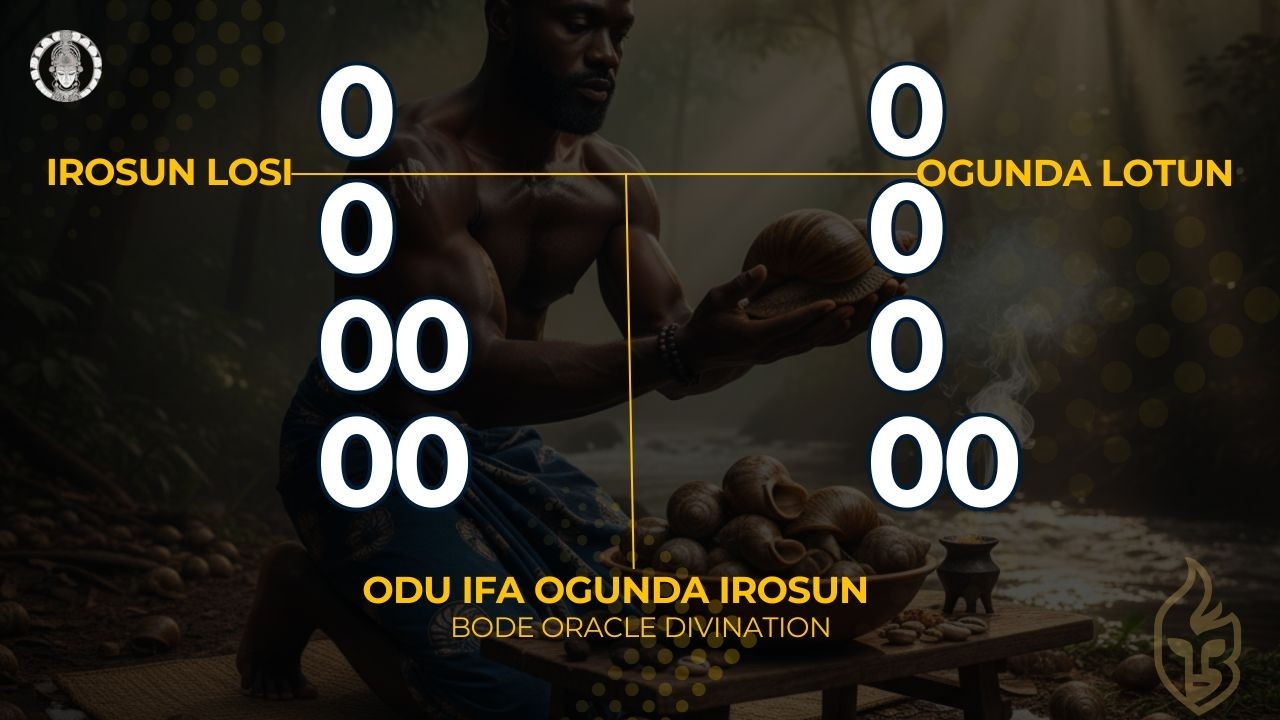

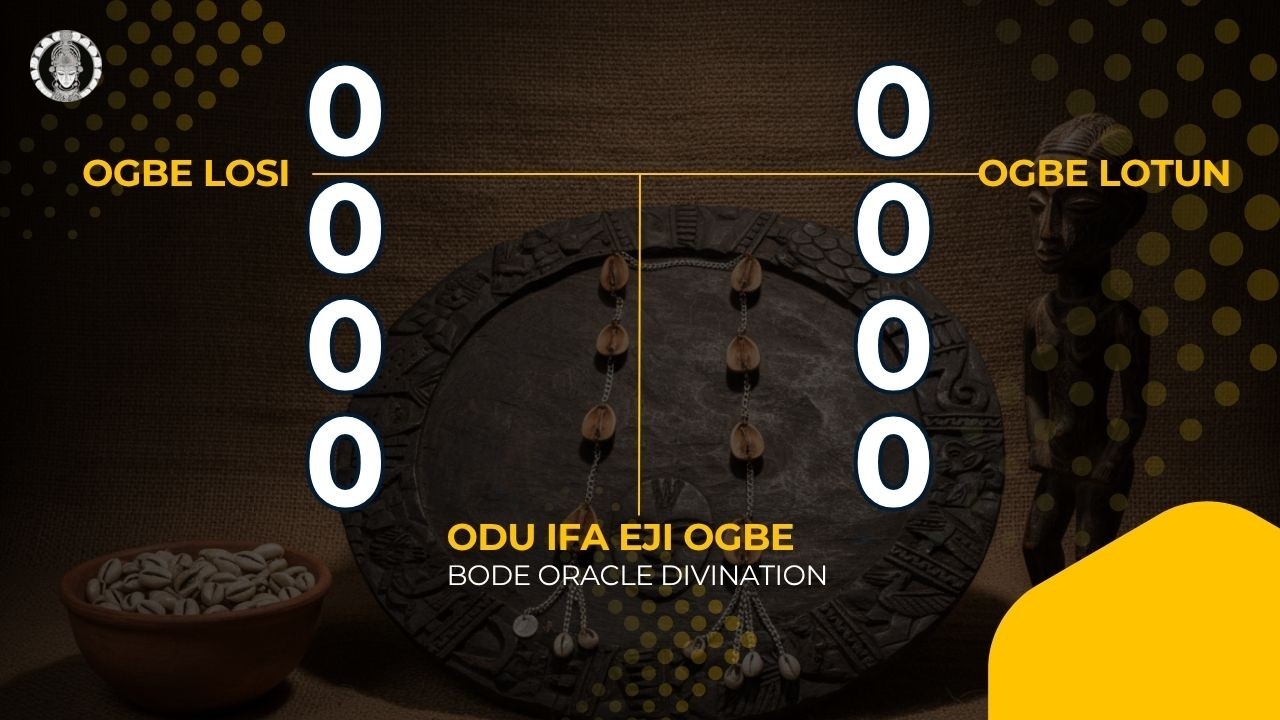

The Complete Obara Corpus: 16 Sacred Divinations

The Obara corpus contains 16 major divinations, each representing Obara's combination with one of the 16 principal Odu. While each carries distinct messages about specific types of strength and courage, all share Obara's fundamental essence of righteous action and moral fortitude. Below is the complete collection with links to detailed explorations of each divination:

Core Teachings of Obara

The Difference Between Courage and Recklessness

One of Obara's most important teachings concerns distinguishing genuine courage from recklessness—understanding that bravery is not absence of fear or wisdom, not blind risk-taking or impulsive action, but rather conscious choice to do what is right despite legitimate fear and full awareness of potential consequences. This distinction is crucial because recklessness masquerading as courage causes tremendous harm while genuine courage serves vital purposes that nothing else can accomplish.

Recklessness involves action without adequate assessment of reality, risks, or consequences. The reckless person acts impulsively, driven by emotion, ego, or the desire to appear brave rather than by actual necessity or moral purpose. They take unnecessary risks, endanger themselves and others needlessly, and confuse adrenaline-seeking with valor. Recklessness often stems from immaturity, insecurity that must constantly prove itself, or lack of imagination about what could go wrong.

Courage, by contrast, involves action despite clear awareness of dangers and difficulties. The courageous person has honestly assessed the situation, recognized legitimate risks, felt appropriate fear, considered alternatives, and chosen to act anyway because the purpose is worthy, the action is necessary, or the alternative is worse. Courage emerges from maturity that can tolerate fear without being paralyzed by it, from principles more important than personal safety, and from love or commitment stronger than self-preservation instinct.

Key differences emerge in several areas. First, in assessment: recklessness skips assessment or minimizes dangers defensively; courage assesses honestly and then acts despite dangers. Second, in purpose: recklessness acts for ego gratification, status, or thrill; courage acts for meaningful purpose beyond self. Third, in consideration of others: recklessness disregards impact on others; courage weighs others' welfare in decisions. Fourth, in timing: recklessness acts impulsively; courage may require immediate action but includes moment of conscious choice rather than pure reaction.

Fifth, in alternatives: recklessness doesn't consider other options; courage acts when alternatives have been considered and found inadequate. Sixth, in proportionality: recklessness applies excessive response; courage matches response to situation. Seventh, in aftermath: recklessness often regrets actions once consequences become clear; courage, while it may suffer consequences, doesn't regret choices made for right reasons. Understanding these differences helps develop genuine courage while avoiding recklessness's pitfalls.

The Warrior's Code of Honor

Obara carries profound teaching about the warrior's code of honor—the ethical framework that distinguishes righteous warrior from mere fighter, that guides use of strength toward worthy ends, and that ensures power serves justice rather than personal gain. This code isn't arbitrary rules imposed from outside but rather wisdom distilled from understanding how strength best serves life, how power can be wielded without corruption, and how force can be applied without becoming oppressor.

The code includes several essential principles. First: Fight only when necessary, not when merely possible. Many conflicts can be avoided, many problems solved without confrontation, many challenges resolved through means other than force. The warrior guided by honor exhausts alternatives before resorting to force, recognizes that every use of strength carries cost, and understands that avoiding unnecessary conflict is wisdom not weakness.

Second: Use minimum force necessary to accomplish righteous purpose. Excessive force reveals lack of control, creates unnecessary harm, escalates conflicts beyond what situation requires, and often backfires by generating sympathy for opponents or resentment from observers. The honorable warrior calibrates response carefully, applying exactly enough strength to achieve necessary outcome without excess that would constitute its own injustice.

Third: Protect the vulnerable and defend those who cannot defend themselves. Warrior strength's highest purpose is protecting life and serving justice, not seeking glory or demonstrating dominance. The honorable warrior uses strength on behalf of others more readily than for personal benefit, stands between harm and those who would be harmed, and accepts personal risk for others' safety as fundamental duty rather than optional choice.

Fourth: Take responsibility for consequences of your actions, including unintended ones. Use of force always creates consequences—some intended, some unforeseen. The honorable warrior doesn't hide from consequences, doesn't blame others for outcomes of their own choices, and accepts accountability even when outcomes weren't what they hoped or intended. This accountability is what separates warrior from mercenary or thug.

Fifth: Respect worthy opponents while opposing them. You can fight fiercely against someone while still respecting their humanity, acknowledging their courage, and treating them with dignity that all persons deserve. The honorable warrior doesn't dehumanize enemies, doesn't glory in their suffering, and doesn't continue harming them beyond what conflict requires. This respect maintains warrior's own humanity and prevents descent into cruelty that ultimately corrupts character.

Sixth: Develop yourself continuously in skills, wisdom, and character. The warrior path is not destination reached but journey continued throughout life. There is always more to learn about strategy, more to understand about when force is truly necessary, more refinement possible in application of strength, and more depth available in ethical understanding. The honorable warrior remains humble student even while being competent practitioner.

Seventh: Serve purposes larger than yourself. Warrior strength divorced from higher purpose becomes violence without meaning. The honorable warrior fights for community, for principles, for protecting what matters, for justice that benefits many rather than just self. This service to something beyond ego is what prevents power from corrupting and what ensures strength is used wisely rather than selfishly.

Confrontation as Sacred Act

Obara presents surprising teaching: confrontation, when done skillfully and for right reasons, can be sacred act—form of honesty that honors truth more than comfort, expression of love that prioritizes long-term wellbeing over short-term peace, and service that refuses to enable harm through silence. This reframes confrontation from purely negative action to potentially positive intervention, from something to avoid at all costs to something sometimes necessary for health and justice.

The teaching recognizes that many problems in relationships, communities, and societies persist precisely because people avoid necessary confrontation. Harmful behaviors continue because nobody challenges them. Injustices remain because confronting them feels too uncomfortable. Patterns repeat because speaking truth about them creates conflict people fear. Individuals suffer because confronting those harming them risks relationship rupture. In each case, avoidance of confrontation—often dressed up as "keeping the peace" or "being compassionate"—actually enables continuation of harm.

Sacred confrontation differs from destructive conflict in several ways. First, it's motivated by care rather than contempt—you confront because you care about the person, relationship, or situation enough to risk discomfort rather than let problems continue. Second, it's about behavior and impact rather than character assassination—you address what someone is doing and its effects rather than attacking who they are as person. Third, it includes vulnerability rather than just accusation—you share how you're affected rather than only condemning other's actions.

Fourth, it seeks resolution rather than revenge—the goal is improving situation, establishing boundaries, or protecting welfare, not punishing offender or proving your superiority. Fifth, it's timely rather than allowing problems to fester until rage erupts—addressing issues when they're still manageable rather than waiting until resentment makes constructive conversation impossible. Sixth, it's direct with the person involved rather than gossiping to others—you speak to the person who can actually address the problem rather than complaining about them to everyone else.

Seventh, it remains open to response rather than merely delivering verdict—you create space for other person to explain, apologize, commit to change, or offer perspective you hadn't considered. Confrontation guided by these principles serves relationship health, personal integrity, and justice in ways that avoidance never can. It clears air, establishes boundaries, stops harmful patterns, and creates opportunity for authentic relationship based on truth rather than comfortable pretense.

However, the teaching also includes wisdom about when confrontation is unwise. Don't confront when person is intoxicated, in crisis, or otherwise unable to engage productively. Don't confront if doing so would endanger your physical safety without adequate protection. Don't confront if you're so emotionally activated you can't communicate skillfully. Don't confront if the person has demonstrated they're genuinely unable to hear feedback rather than merely unwilling. Don't confront if your actual goal is venting anger rather than addressing problem. Wisdom involves knowing both when to confront and when to refrain.

The Teaching of Controlled Fire

Obara uses the metaphor of fire to teach about strength and its proper use: fire provides warmth, light, and transformation; enables cooking, metalworking, and countless human endeavors; but uncontrolled becomes wildfire destroying everything in its path. Similarly, strength controlled and directed wisely serves countless good purposes, but strength uncontrolled becomes destructive force harming indiscriminately. The teaching asks: Are you the master of your fire or is your fire master of you?

Many people struggle with controlling their "inner fire"—their anger, aggressive impulses, competitive drive, or assertive energy. Some suppress it completely, afraid of their own strength, resulting in passivity, inability to defend themselves, and accumulation of resentment that eventually explodes. Others let it burn uncontrolled, reacting immediately to every provocation, hurting people they care about, and creating ongoing conflict. Neither approach represents the warrior's wisdom that Obara teaches.

Controlling fire doesn't mean extinguishing it. Your anger, assertiveness, and strength are not enemies to eliminate but forces to harness. The teaching involves several capacities working together. First, awareness of your fire—noticing when anger arises, recognizing your aggressive impulses, feeling your warrior energy without immediately acting on it. This awareness creates space between impulse and action, between feeling and response.

Second, acceptance of your fire as natural part of being human. Anger is not sin; it's emotion signaling that boundaries have been violated or injustice has occurred. Aggressive impulses are not evil; they're protective instincts that served survival throughout human evolution. Warrior energy is not problem; it's capacity for action and strength. Rejecting these as fundamentally bad creates internal division and shame that actually prevents skillful use.

Third, direction of your fire toward appropriate targets for worthy purposes. Use anger to fuel action against injustice rather than lashing out at whoever is nearby. Channel aggressive energy into protecting vulnerable rather than dominating equals. Direct warrior spirit toward meaningful challenges rather than picking unnecessary fights. Your fire becomes sacred when burned for purposes beyond ego.

Fourth, modulation of your fire according to what situations actually require. Sometimes you need full blaze; sometimes just glowing coals; sometimes fire banked low; sometimes complete cooling. Developing capacity to turn fire up or down consciously rather than having only "off" or "raging" is crucial skill. This modulation allows proportionate response, prevents exhaustion from burning constantly at high intensity, and maintains relationships that constant blazing would destroy.

Fifth, tending your fire with ongoing attention. Fire left completely unattended dies or spreads destructively. Fire tended skillfully provides sustained benefit. This means regularly checking in with your anger, aggressive impulses, and warrior energy—not to suppress them but to ensure they're being used wisely, to address issues before they become explosive, and to maintain connection with your strength rather than disconnecting from it.

Strength in Service and Servant Leadership

Perhaps Obara's most mature teaching concerns strength in service—the understanding that power reaches its highest expression not when wielded for personal gain but when deployed for others' benefit, that the strongest warriors are those whose strength serves rather than dominates, and that true leadership is fundamentally about service rather than status. This teaching directly challenges cultural narratives that equate strength with self-interest and power with dominance.

Strength in service manifests in multiple ways. The parent uses their greater strength to protect, provide for, and enable child's flourishing rather than to control or intimidate. The teacher uses their knowledge and authority to empower students rather than to maintain superior status. The leader uses their position to serve community's needs rather than personal ambitions. The friend uses their capabilities to support others through difficulty rather than to gain advantage. In each case, strength flows outward in service rather than inward in accumulation.

This orientation requires specific internal shifts. First, it requires ego that finds satisfaction in others' success rather than needing to be superior. The servant leader genuinely celebrates when those they serve flourish, succeed, or even surpass leader's own achievements. This celebration isn't performance or spiritual bypass but authentic joy in others' growth. Second, it requires security that doesn't need constant validation through dominance. The person whose strength serves is strong enough not to need to prove strength constantly.

Third, it requires understanding that giving strength away actually increases it rather than depleting it. This seems counterintuitive—shouldn't using strength for others exhaust you? But Obara teaches that strength, unlike material resources, actually grows through generous use for worthy purposes and diminishes through selfish hoarding or misuse. The more you deploy your strength in service, the stronger you become. The more you withhold it out of fear of depletion, the weaker you grow.

Fourth, it requires wisdom about healthy service versus unhealthy self-sacrifice. Strength in service doesn't mean martyring yourself, enabling others' dysfunction, or giving beyond your capacity until you break. Healthy service maintains boundaries, requires reciprocity in relationships, knows when to step back, and recognizes you cannot serve effectively from depleted state. The teacher who burns out serving students can no longer teach; sustainable service includes self-care.

The teaching reveals that servant leadership is actually more challenging than domination-based leadership. Domination relies on force, fear, and control—relatively simple tools that don't require much sophistication. Servant leadership requires wisdom to know what truly serves, strength to do what's right rather than what's easy, humility to prioritize others' needs, skill to empower rather than control, and patience to see long-term flourishing as measure of success rather than immediate compliance.

Organizations, families, and communities led by servant leaders develop differently than those led by dominators. Servant-led groups develop distributed strength—many people become capable and confident. Dominator-led groups develop concentrated weakness—followers become dependent, fearful, and incapable of independent action. Servant-led groups innovate and adapt well because many minds contribute. Dominator-led groups stagnate because only leader's ideas matter. Servant-led groups continue functioning if leader leaves. Dominator-led groups collapse without their dominator.

Practical Guidance for Working with Obara

When Obara Appears in Your Divination

If any Obara Odu appears in your Ifa consultation, it signals that courage, strength, or decisive action are currently priority concerns. Here is how to work effectively with Obara energy:

1. Assess Where Courage Is Required

The first response is honest assessment of where in your life courage and strength are currently needed. This might be obvious—a confrontation you've been avoiding, a boundary you need to establish, or a stand you must take. Or it might be subtle—noticing where you've been passive when action was needed, where you've stayed silent when truth-speaking was required, or where you've avoided responsibility you should accept. Ask yourself: Where am I being called to greater courage? What am I avoiding that needs confronting?

2. Perform the Prescribed Rituals Immediately

Obara sacrifices are particularly important for strengthening your warrior spirit, protecting you during confrontations, and ensuring your strength serves righteous purposes rather than ego gratification. These might include offerings to Ogun (Orisha of iron, war, and work), Shango (Orisha of thunder, justice, and power), or other deities associated with warrior energy. The rituals help align your personal strength with divine purpose and protect you from misusing power. Work with a qualified Babalawo to ensure proper performance.

3. Distinguish Between Righteous Action and Ego Reaction

Before taking strong action, examine your motivations honestly. Are you acting from righteous purpose—defending principles, protecting others, establishing necessary boundaries, or speaking important truth? Or are you reacting from ego—seeking revenge, proving superiority, venting anger, or dominating others? This distinction is crucial. Obara strength serves righteous purposes; ego-driven force creates problems even when it feels momentarily satisfying. If needed, consult trusted advisors who can reflect perspectives you might miss when emotionally activated.

4. Prepare Thoroughly Before Acting

Courage doesn't mean acting impulsively without preparation. When possible, prepare for confrontations, boundary-setting, or difficult conversations. Consider what you want to say, anticipate likely responses, plan how to handle various scenarios, and ensure you have support systems in place. This preparation isn't cowardice but wisdom—the warrior who fails to prepare often fails in action. However, don't let desire for perfect preparation become excuse for indefinite delay. There's balance between reckless haste and paralyzing perfectionism.

5. Act Decisively When Action Is Required

Once you've assessed honestly, consulted properly, and prepared adequately, act decisively rather than continuing to hesitate. Many people correctly identify what needs doing but then delay indefinitely, hoping situations will resolve themselves or becoming paralyzed by anxiety. Obara teaches that some situations improve only through direct action, that courage means acting despite fear rather than waiting until fear disappears, and that decisive action, even if imperfect, often serves better than perfect planning that never translates to action.

6. Maintain Boundaries Consistently

If Obara is calling you to establish or defend boundaries, recognize this is ongoing practice rather than one-time action. Boundaries require consistent maintenance—you must uphold them each time they're tested, not just establish them initially and then abandon them when maintaining them becomes uncomfortable. Expect that people accustomed to violating your boundaries will test new limits repeatedly. Your consistency in maintaining boundaries teaches others to respect them and teaches you that boundary-setting is sustainable.

7. Seek Support for Your Warrior Journey

Don't walk the warrior path in isolation. Connect with others who embody courage and strength in ways you admire. Join or create communities that support righteous action rather than passive acceptance of injustice. Work with mentors who can guide development of your warrior spirit. Seek counseling or therapy if you're working through issues that make courage difficult—trauma, shame, or fear-based patterns. The warrior tradition has always involved training, mentorship, and community; solo heroism is myth more than reality.

Daily Practices for Developing Warrior Spirit

Cultivating authentic Obara energy requires regular practice, not just crisis-moment action. These daily practices build warrior capacity:

Physical Strength Training: Engage in practices that build physical strength, stamina, and capability. This might be weightlifting, martial arts, running, yoga, or any physical discipline that challenges your body. Physical practice develops not just muscles but qualities that transfer to other domains: discipline, persistence through discomfort, capacity to push beyond where you thought your limits were, and confidence that comes from capability. Your body is warrior's primary instrument; keeping it strong and capable is fundamental.

Courage Practice: Deliberately practice small acts of courage daily. Speak up in a meeting when you'd normally stay quiet. Have a difficult conversation you've been avoiding. Try something that scares you slightly. Say no to a request that violates your boundaries. These small practices build courage capacity that becomes available for larger challenges. Like muscles growing through progressive resistance, courage grows through progressive challenge.

Morning Warrior Meditation: Begin each day with meditation or contemplation connecting you to warrior energy. This might involve visualization of yourself as strong, capable, and courageous. Remembrance of times you acted bravely. Invocation of warrior deities or ancestors. Setting intention to act with strength and integrity throughout the day. Or simply sitting with awareness of your own power and capacity. This practice aligns you with warrior energy before daily challenges arise.

Boundary Awareness Practice: Develop ongoing awareness of your boundaries—noticing when they're honored or violated, observing your responses, and practicing maintaining them in small ways before major challenges require it. Throughout your day, notice: Are you saying yes when you mean no? Are you accepting treatment you find unacceptable? Are you allowing violations you should address? This awareness is prerequisite for skillful boundary-setting.

Evening Reflection on Courage: Each evening, reflect on your day through lens of courage: Where did I act courageously? Where did I avoid acting when action was needed? What opportunities for courage did I notice? What did I learn about my relationship with strength? This reflection builds self-knowledge about your patterns and celebrates growth while noting areas needing development. Over time, you'll notice evolution in your capacity and choices.

Study of Warrior Traditions: Regularly read about or study warrior traditions from various cultures—martial arts philosophies, military strategy, indigenous warrior traditions, or biographies of people who embodied moral courage. This study provides models, inspiration, and frameworks for understanding warrior energy. However, study should lead to practice; knowledge without application remains sterile.

Navigating Specific Courage Challenges

Obara energy manifests differently across various life domains, each requiring particular approaches:

Confronting Injustice: When you witness or experience injustice, Obara calls you to address it rather than remaining passive. This doesn't always mean dramatic confrontation—sometimes it involves filing formal complaints, documenting problems systematically, organizing collective response, or strategic advocacy. Consider what approaches are most likely to create actual change rather than just expressing your anger. Seek allies who share your concerns. Protect yourself legally and socially when taking on powerful systems. And recognize that confronting injustice is marathon not sprint; sustainable activism requires pacing.

Setting Boundaries in Relationships: When people you care about violate your boundaries, responding with Obara energy means clear, firm communication combined with genuine care. "I love you AND I won't accept this treatment" is more powerful than either "I love you so I must accept this" or "I won't accept this so I must leave." Explain boundaries clearly, state consequences for violations, and follow through consistently. Don't apologize for having limits or over-explain simple boundaries. And recognize that some people will respect boundaries once you establish them while others will require distance or separation if they persistently refuse to respect your limits.

Speaking Difficult Truths: When truth needs speaking despite discomfort, prepare by getting clear about what truth actually is (versus your interpretation or judgment), choosing timing when the person can actually hear rather than when you're most angry, focusing on specific behaviors and impacts rather than character attacks, and remaining open to their response rather than just delivering verdict. Remember that speaking truth is your responsibility; how they respond is theirs. You cannot control their reaction but you can control your delivery to maximize possibility of being heard.

Taking Leadership: When situations require someone to take charge and you're positioned to do so, step forward despite discomfort or self-doubt. Leadership often goes to those willing to accept responsibility rather than those most qualified. Once in leadership role, focus on serving those you lead rather than proving your authority, making decisions based on what's best rather than what's popular, and developing others' capacity rather than keeping them dependent. And remember that leadership includes delegating—you don't need to do everything yourself; you need to ensure everything gets done.

Defending Others: When you witness someone being harmed, mistreated, or unjustly attacked, Obara calls you to intervene appropriately. This might mean speaking up in the moment, reporting to authorities, offering support privately, or organizing collective response. Consider your capacity, resources, and what will actually help versus what might escalate harm. Sometimes direct intervention is needed; sometimes supporting the person to defend themselves serves better; sometimes systemic response through institutions is most effective. The key is not allowing harm to continue through your silence or passivity.

Working with Resistance to Your Own Strength

Many people struggle not with lack of strength but with resistance to owning and using their strength. This resistance has various sources and requires different approaches:

If You Were Taught Strength Is Wrong: Some people, especially women and those from marginalized groups, were taught that strength, anger, or assertiveness are inappropriate, unfeminine, or dangerous. This conditioning runs deep and overcoming it requires conscious reclamation. Practice saying no without explanation. Express anger when situations warrant it. Take up space physically and socially. Notice when you're minimizing yourself or your needs. And surround yourself with people who support your strength rather than punishing it.

If You Fear Becoming an Abuser: Some people who experienced abuse fear that accessing their own strength will turn them into abusers. This fear, while understandable, conflates strength with abuse. Abusers misuse strength; that doesn't make strength itself problematic. The fact that you worry about becoming abusive actually suggests you won't—abusers rarely have such concerns. Work with therapist to distinguish between healthy strength and abusive behavior, practice using strength in small ways to build confidence that you can control it, and study examples of people who embody strength without cruelty.

If You've Been Punished for Being Strong: If past expressions of strength resulted in rejection, punishment, or loss, you may have learned to suppress strength for self-protection. This is adaptive response to unsafe situations. As adult in different circumstances, reassess whether current environment actually punishes your strength or whether you're operating from outdated protective patterns. Test expressing strength in small, safe ways. Build relationships with people who welcome rather than fear your power. And recognize that some relationships or environments genuinely are unsafe for your full strength; wisdom includes knowing when to express and when to protect yourself through strategic restraint.

If You Don't Know Your Own Strength: Some people have never actually tested their capacity and therefore underestimate their own strength. This manifests as perpetual self-doubt, assuming you can't handle things you've never tried, and defaulting to helplessness. The remedy is graduated exposure—deliberately taking on challenges slightly beyond your comfort zone, noticing that you handle them, and progressively expanding what you know you can do. Physical training provides tangible evidence of increasing capacity that generalizes to other domains.

Signs You're Embodying Obara Successfully

How do you know if you're working with Obara energy skillfully? These signs indicate healthy warrior development:

You're able to act decisively when action is required while also exercising restraint when restraint serves better. You speak uncomfortable truths when necessary while maintaining compassion for those receiving truth. You defend your boundaries consistently without needing to be aggressive or cruel about it. You stand up for others who are being mistreated rather than remaining silent bystander. You take responsibility for your choices and their consequences rather than blaming or deflecting.

You can feel anger fully without being controlled by it or acting destructively from it. You're comfortable with your own power and strength rather than either suppressing them or wielding them clumsily. You lead when leadership is needed rather than always deferring to others. You're willing to be temporarily unpopular for doing what's right rather than prioritizing approval over integrity. You use your strength in service of principles and people you care about rather than for ego gratification.

You're developing physical capability alongside moral capacity. You can tolerate conflict and confrontation when necessary without either seeking them unnecessarily or avoiding them compulsively. You maintain boundaries without excessive guilt or anxiety. And importantly, you're balancing strength with other qualities—wisdom, compassion, humility—rather than developing warrior energy in isolation from other aspects of mature character.

When to Seek Professional Guidance

Certain situations require professional guidance from qualified Ifa priests or other appropriate professionals:

Seek Ifa divination and priestly support when you need clarity about whether specific action is righteous or ego-driven, when you're facing major confrontation or conflict requiring spiritual protection and guidance, when prescribed Obara rituals require proper performance by initiated practitioners, when you need ongoing support navigating complex situations requiring sustained courage, when you're unclear how to balance strength with compassion in specific circumstances, or when you need help understanding what Obara's appearance in your reading means for your particular situation.

Seek mental health support when past trauma makes accessing your strength extremely difficult or triggering, when your relationship with anger or aggression feels out of control, when you struggle with chronic passivity or inability to defend yourself despite wanting to change, when you notice patterns of self-sabotage whenever you start becoming stronger, or when developing warrior energy is bringing up deep psychological material requiring professional support to process safely.

Seek legal counsel when confronting injustice that could have legal ramifications, when establishing boundaries with people who might retaliate through legal means, or when you're unsure about legal protections available to you in specific situations. Courage doesn't mean acting without appropriate professional guidance when that guidance would protect you and increase your effectiveness.

The Bode Oracle platform connects you with experienced Babalawos who can provide authentic Obara divination, prescribe and perform rituals that strengthen warrior spirit and protect during confrontations, teach you specific practices for developing courage and righteous strength, offer ongoing guidance through complex situations requiring sustained fortitude, and help you distinguish between righteous action and ego-driven reaction. Working with qualified practitioners ensures you develop warrior energy in alignment with traditional wisdom rather than personal interpretation that might lead astray.

Additional Resources

Explore Individual Obara Divinations

For detailed information about each specific Obara Odu, visit these dedicated pages:

- Obara Ogbe - Complete Guide

- Obara Oyeku - Detailed Teachings

- Obara Iwori - Sacred Verses

- Obara Odi - Divination Guide

- Obara Irosun - Spiritual Wisdom

- Obara Owonrin - Complete Commentary

- Obara Meji - Sacred Teachings

- Obara Okanran - Divination Verses

- Obara Ogunda - Spiritual Guide

- Obara Osa - Complete Analysis

- Obara Ika - Sacred Wisdom

- Obara Oturupon - Detailed Guide

- Obara Otura - Divination Teachings

- Obara Irete - Complete Commentary

- Obara Ose - Sacred Verses

- Obara Ofun - Spiritual Guidance

General Ifa and Yoruba Spirituality Resources

More BODE Resources

- All About the 16 Odu Ifa and Their Meaning

- Complete Odu Library - All 256 Odu

- Bode Oracle Blog - Extensive Ifa Articles

- Bode Oracle Home - Divination Services & Community

External Academic and Cultural Resources

- UNESCO: Ifa Divination System - Intangible Cultural Heritage

- UNESCO Archives: Ifa of the Yoruba People of Nigeria

- Duquesne University: African Traditional Religions - Ifa Divination

- ScienceDirect: Algebraic Characterization of Ifa Divination Codes

- Wikipedia: Ifa - Overview and History

- Wikipedia: Opon Ifa (Divination Tray)

Bode Oracle Social Media and Video Content

- BODEOracle YouTube Channel - Video Teachings

- BODEOracle TikTok - Short Spiritual Content

- BODEOracle Facebook - Community Discussions

- BODEOracle X (Twitter) - Daily Wisdom

- BODEOracle Pinterest - Visual Content

Join the Bode Oracle Community: Visit Bode.ng to access authentic Ifa divination services, connect with qualified Babalawos, participate in spiritual discussions, and deepen your understanding of Yoruba spirituality. Register today for exclusive content, personalized guidance, and connection with a global community of Ifa practitioners and learners.

Frequently Asked Questions About Odu Obara

Find answers to common questions about this powerful Odu and its spiritual significance

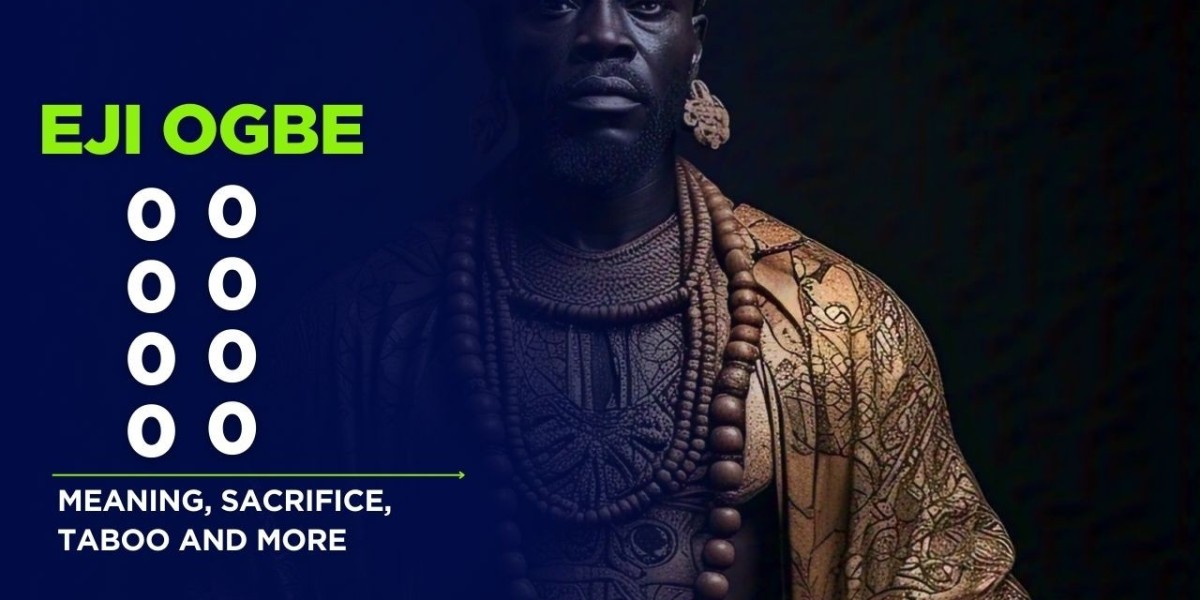

Odu Obara is the seventh of the 16 principal Odu in the Ifa divination system. It represents warrior spirit, moral courage, righteous action, and the strength to stand firm in truth. Obara embodies the principle of taking decisive action when necessary, defending what is right even when difficult, and the courage to confront challenges directly.

When Obara appears in divination, it signals times requiring strength and courage, situations demanding clear boundaries and firm action, the need to defend oneself or others, or moments calling for righteous confrontation. The Obara corpus contains 16 major divinations addressing every aspect of courage, strength, and moral action in human experience.

Obara symbolizes the principle of righteous strength—the understanding that true courage involves not just physical bravery but moral fortitude, that real power includes knowing when to act and when to restrain, and that strength without wisdom becomes mere violence. It represents the warrior who fights for justice, the protector who defends the vulnerable, the leader who takes responsibility, and the truth-teller who speaks despite consequences.

Spiritually, Obara teaches that some situations require firm action rather than passive acceptance, that boundaries must sometimes be defended forcefully, and that courage means acting according to truth even when afraid. Obara is associated with moral integrity, decisive action, protective energy, warrior spirit, and the strength to do what is right rather than what is easy.

The Obara family consists of 16 major Odu divinations: Obara Ogbe, Obara Oyeku, Obara Iwori, Obara Odi, Obara Irosun, Obara Owonrin, Obara Meji (Obara-Obara), Obara Okanran, Obara Ogunda, Obara Osa, Obara Ika, Obara Oturupon, Obara Otura, Obara Irete, Obara Ose, and Obara Ofun.

Each carries distinct messages about different types of strength and courage while maintaining Obara's core essence of righteous action. Together, they form a complete system addressing moral courage, protective strength, righteous confrontation, and the wisdom of knowing when to fight and when to yield.

Obara teaches the crucial distinction between righteous strength and destructive aggression. True Obara strength is rooted in moral purpose—defending truth, protecting the vulnerable, maintaining necessary boundaries, or confronting injustice. It is measured, purposeful, and proportionate to the situation. Aggression, by contrast, is reactive, excessive, and often rooted in ego, fear, or the desire to dominate.

Obara strength asks "What is right?" while aggression asks "How can I win?" Obara teaches that the warrior who cannot control their own strength is not truly strong, that power without wisdom is dangerous, and that the highest form of strength often involves restraint—knowing you could act forcefully but choosing not to when force isn't necessary.

When Obara appears in divination, it signals that courage and decisive action are required. The appropriate response involves: honestly assessing where you need to stand firmer or take clearer action, performing the prescribed sacrifices and rituals to strengthen your warrior spirit, establishing or defending necessary boundaries in your life, speaking truth even when uncomfortable, taking responsibility for situations under your authority, seeking guidance from qualified Ifa priests, and distinguishing between righteous action and reactive aggression.

Obara teaches that avoiding necessary confrontation causes as many problems as seeking unnecessary conflict, that true strength includes knowing when to act and when to restrain, and that courage means doing what is right despite fear rather than acting without fear.

Obara teaches several essential lessons about courage: First, courage is not the absence of fear but action despite fear. Second, moral courage (standing for truth, defending principles) often requires more strength than physical courage. Third, true courage includes restraint—knowing when not to fight is as important as knowing when to fight. Fourth, courage without wisdom becomes recklessness, while wisdom without courage becomes cowardice.

Fifth, protecting boundaries is not selfishness but necessary self-care and respect. Sixth, some situations improve only through direct confrontation, not avoidance. Seventh, the warrior's highest purpose is protecting life and justice, not seeking glory or dominance. Obara reveals that developing warrior spirit is lifelong practice requiring continuous refinement of strength, wisdom, and moral clarity.